Secret Nazi X-Planes.

The Horten Ho 229 Flying Wing.

The German government was funding glider clubs at the time because

production of military aircraft was forbidden by the Treaty of

Versailles after World War I. The flying wing layout removes any

"unneeded" surfaces and, in theory at least, leads to the lowest

possible drag.

The H0-229 evolved from the Ho-IX and is just one a whole series of

Fiddlersgreen flying wings.

The German government was funding glider clubs at the time because

production of military aircraft was forbidden by the Treaty of

Versailles after World War I. The flying wing layout removes any

"unneeded" surfaces and, in theory at least, leads to the lowest

possible drag.

The H0-229 evolved from the Ho-IX and is just one a whole series of

Fiddlersgreen flying wings.

The first Horten wing

(a glider as were many of their designs), flew in 1934 and their

devotion to the design carried them on even after the war. What is truly

amazing about their story is that often their work was done in secret,

even from the Luftwaffe, who did not want a new design interfering with

other types.The final design they were working on during the closing

days of the war was Ho 229 that would be able to carry two atomic bombs to the U.S. and return.

The first Horten wing

(a glider as were many of their designs), flew in 1934 and their

devotion to the design carried them on even after the war. What is truly

amazing about their story is that often their work was done in secret,

even from the Luftwaffe, who did not want a new design interfering with

other types.The final design they were working on during the closing

days of the war was Ho 229 that would be able to carry two atomic bombs to the U.S. and return.

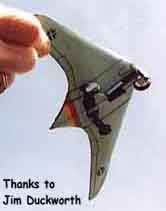

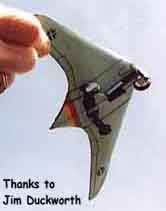

Chauncy Green has designed this really accurate yet easy to build model which, we hope, is the start of a long and intriguing line of Nazi Luftwaffe Secret X-planes..Perhaps it's the start of a collection of flying wings..

What people say... Hallo, Just to mention that the designer of the flying wing mentioned in your site is Reimar Horten and not Horton. There is a Horton. He designed a low aspect ratio after WW2. It is called "wingless airplane".The error you made happens a lot. Another error which happens too is to name the jet flying wing the Horten Ho IX. It should be Horten H IX Hope this will help. Keep that brain spawning wings (usual end-phrase), Koen Van de Kerckhove , Belgium, Europe(2-01)

I just finished the Horten wing. What a great job of making a difficult

subject easy to build! I found that stuffing a wad of tissue in the

center section made it easier to attach the wings. I have built way too

many of these thins already, but don't intend to stop any time soon.

Thanks for all the hard work.Ed (April 23, 01)

Horton looks great!!! but I see some people have had trouble getting the

wings right , here is my slant on it. build the center section and add

all the engine parts but leave off the under carriage doors , cut a

access hole as suggested where the big plate will sit at the back

leaving a 1/8 inch lip all around opening I prefer mine without U/C.

Prepare each wing by lightly score the leading edge and score the big

tab on the bottom of the wing then cutoff all the little tabs ! trust me

on this ! bend the wing halves and the large tab so they are at 90

degrees but not further. Now glue just the large tab on the lower wing

to the upper wing ,at this point ensure the wingtip/trailing edge line

up properly and if necessary insert something into the wing to stop the

wing skins from becoming glued together.When this has dried gently pop

open the wingtip apply glue and glue the tips together.

Take one wing and apply glue to the body along where the top of the wing will go and at the front just around the small tabs but no further , now attach the top of the wing concentrating on getting the front right and the paint scheme lined up and follow it down to the trailing edge. Start at the front underneath and do the same for the lower part of the wing and when this has dried put some glue in the remaining gap ( where the tabs were cut from and seal up the wing. Whew done ! Large model paper 80gm , paper just strong enough ) How can you get so much fun from a single sheet of paper ! Paul Needham .

Take one wing and apply glue to the body along where the top of the wing will go and at the front just around the small tabs but no further , now attach the top of the wing concentrating on getting the front right and the paint scheme lined up and follow it down to the trailing edge. Start at the front underneath and do the same for the lower part of the wing and when this has dried put some glue in the remaining gap ( where the tabs were cut from and seal up the wing. Whew done ! Large model paper 80gm , paper just strong enough ) How can you get so much fun from a single sheet of paper ! Paul Needham .

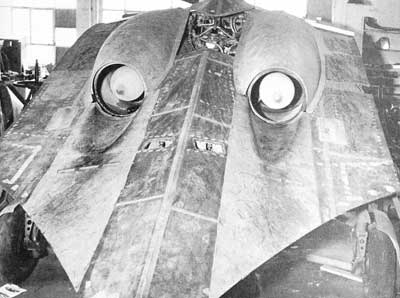

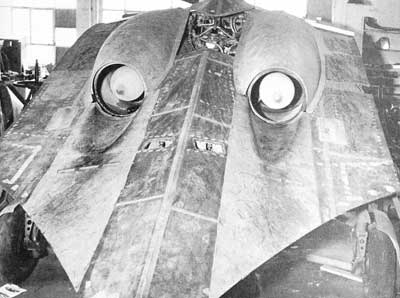

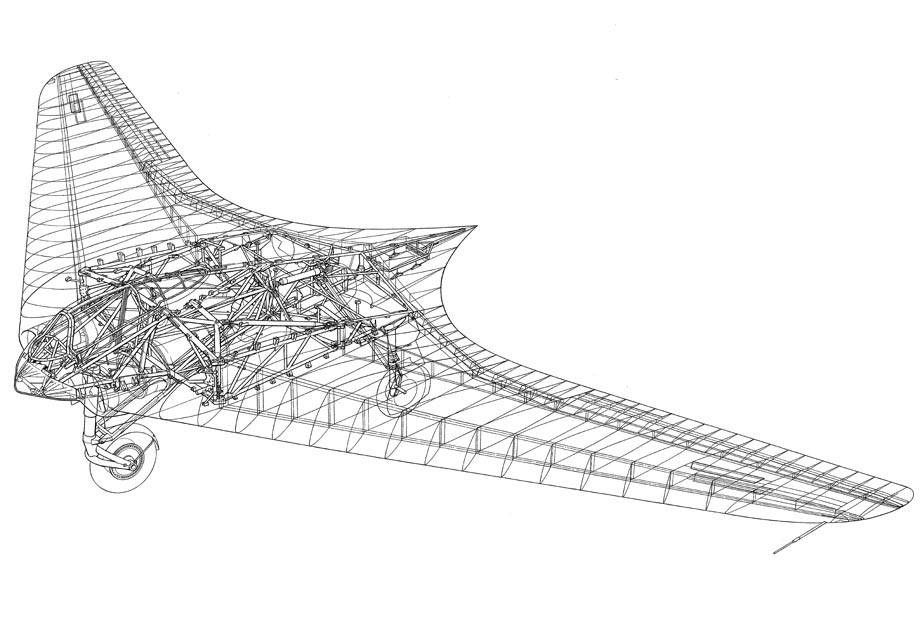

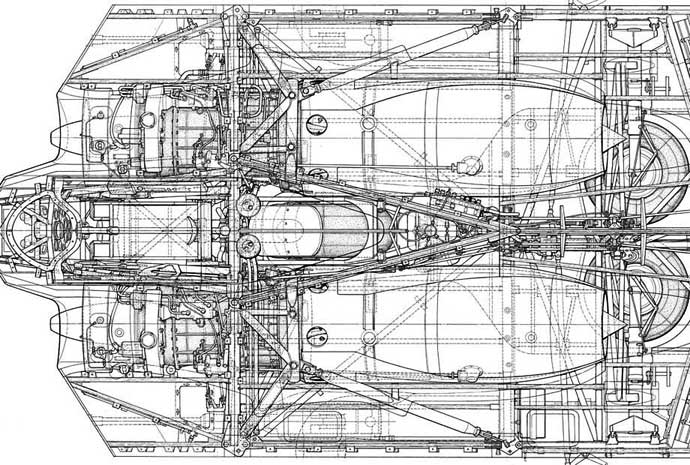

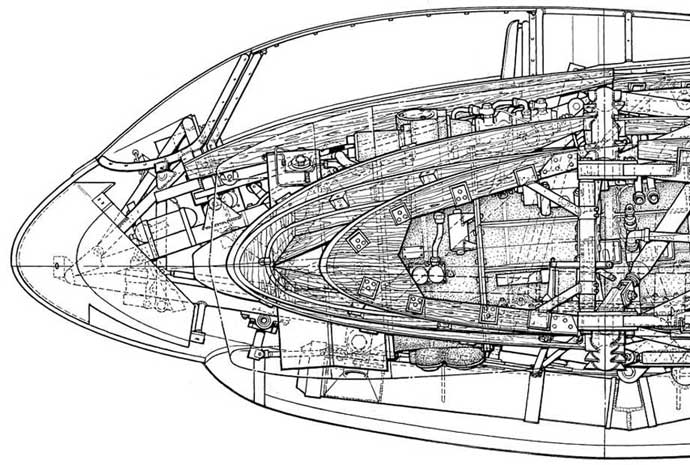

The Ho-IX V3 was an unarmed, twin-jet, single aircraft.

Further production of the fighter bomber was assigned to the Gothaer

Waggon Fabrik (GWF). Well-known for its Go 241 cargo glider, Gotha

was considered the company best suited to manufacture Horten aircraft.

The aircraft's turbojet engines were installed splayed 15 degrees

left and right of the aircraft centerline and 4 degrees nose down.

The new installation was tested in a center section mock-up. Construction

of the Ho-IX V3 was nearly complete when the Gotha Works at Friederichsroda

was overrun by troops of the American 3rd Army's VII Corps on

April 14, 1945. The aircraft was assigned the number T2-490 by

the Americans. The aircraft's official RLM designation is uncertain,

as it was referred to as the Ho 229 as well as the Go 229. Also

found in the destroyed and abandoned works were several other

prototypes in various stages of construction, including a two-seat

version.

The V3 was sent to the United States by ship, along

with other captured aircraft, and finally ended up in the H. H.

"Hap" Arnold collection of the Air Force Technical Museum.

The all-wing aircraft was to have been brought to flying status

at Park Ridge, Illinois, but budget cuts in the late forties and

early fifties brought these plans to an end. The V3 was handed

over to the present-day National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in

Washington D.C.

In spite of the fact that only two prototypes were

actually completed and flown, the Horten brothers' all-wing, jet powered

fighter, initially known as the H IX, was high on the list of

fighters officially sanctioned for continued development, production

and even operational deployment to a specific Luftwaffe unit.

None of this would likely have resulted, had it not been for a

number of fortuitous events which ultimately positioned the brothers

within the higher circles of the Luftwaffe. The H IX development

began early in 1943, when the Horten brothers first met Reichsmarschall

Hermann Goring and Oberstleutnant i.G.(Lt. Col.) Diesing at the

Reichsjagerhof (Reich hunting lodge) on September 28, 1943. Having

shown Reichsmarschall Goring some photographs, 30-year old Hauptmann

(Captain) Walter Horten outlined the evolution of the new fighter

by his team, which included Messrs. Kaupa and Peschke. He indicated

the new fast fighter would also be able to carry a 2,200 lb. bomb at a top speed of approximately 590 mph.

As planned, the un-powered Horten Ho 229 V1 was towed

into the air at Gottingen by an He 45 on March 1,1944, with Lt.

Heinz Scheidhauer at the controls. Later, a larger twin engine

He 111 took over the task of towing from the small He 45. Meanwhile,

work progressed on the first powered prototype, the Ho 229 V2,

until it was realized that the promised BMW 003 would not be ready.

Accordingly, the decision was made to modify the design to allow

for the installation of two larger Jumo 004 turbojets.

When the first Jumo 004B units were delivered, the Horten brothers were astonished to learn that their diameter turned out to be nearly 8 inches greater than anticipated. The design had to be modified once again. The wingspan was increased from 52.98 ft. to 69.9 ft. in order to improve the aerodynamic qualities of the flying wing.

When the first Jumo 004B units were delivered, the Horten brothers were astonished to learn that their diameter turned out to be nearly 8 inches greater than anticipated. The design had to be modified once again. The wingspan was increased from 52.98 ft. to 69.9 ft. in order to improve the aerodynamic qualities of the flying wing.

On June 26, 1944, Luftwaffenkommando IX began construction

of the redesigned and improved Ho 229 V3, as well as additional

test aircraft began at a small Fliegerhorst (air base) near the

city of Gottingen. The technicians worked long hours,often putting

in more than ninety hours per week, in an effort to finalize the

installation of the turbojets.

Meanwhile, on July 7, 1944, the Deutsche Versuchsanstalt fur

Luftfahrt (DVL) at Berlin-Adlershof had finished flight testing

the Ho 229 V1. Flight testing was not entirely satisfactory due

to the aircraft's excessive yaw (side-to-side movement), but overall,

control surfaces were considered to be sufficient.

Two months later, the list of equipment for the full-scale

mockup was compiled by Oberleutnant Bruning (Dept. E 2, Rechlin),

Brune (Horten), Huhnerjager (Gotha), and some other experts. The

production Ho 229 was supposed to have been equipped with FuG

25a, FuG 16ZY, and FuG 125 avionics. It was also planned to fit

two or four forward firing fixed weapons as well as reconnaissance

equipment comprising an Rb 50/30 or Rb 75/30 aerial camera.

The first unofficial flight, with Lieutenant (2nd Lt.) Erwin

Ziller at the controls, took place on December 18, 1944. As one

of the Horten brothers later recalled, this was the first flight

of one of their designs under jet power.

Because of Reichsmarschall Goring's influence the Ho 229 was

included in the Jager-Notprogramm (fight emergency program).

On September 21, 1944, the first forty production Ho 229 A-1s

were ordered. These were to be built by Gothaer Waggonfabrik74

Initially, the firm of Klemm, located at Boblingen, near Stuttgart,

was supposed to build twenty Ho 229s. Gotha was to build an additional

twenty aircraft. During late 1944, initial attempts to set up

a small production line near Gotha failed to materialize. During

this period, Mobel May, a small furniture firm near Tamm in Wurttemberg,

was brought into the program to manufacture wooden wing sections.

The fate of the Ho 229 V2's test pilot, Erwin Ziller, was sealed

when a flame-out occurred on February 26, 1945, during the landing

approach of his fourth flight. Unable to recover, Ziller crashed,

destroying the prototype. When the US 3rd Army Corps reached the

Gotha plant on April 14, 1945, three Ho 229 prototypes (V4, V5

and V6) were discovered in various stages of construction. The

Ho 229 V1 was captured at Leipzig. The Ho 229 V3, which was under

construction at the end of the war, was also seized, and was subsequently

shipped to the USA for evaluation.

The first unofficial flight, with Leutnant (2nd Lt.) Erwin

Ziller at the controls, took place on December 18, 1944. As one

of the Horten brothers later recalled, this was the first flight

of one of their designs under jet power.

Because of Reichsmarschall Goring's influence the Ho 229 was

included in the Jager-Notprogramm (fighteiemergency program).

On September 21, 1944, the first forty production Ho 229 A-1s

were ordered. These were to be built by Gothaer Waggonfabrik74

Initially, the firm of Klemm, located at Boblingen, near Stuttgart,

was supposed to build twenty Ho 229s. Gotha was to build an additional

twenty aircraft. During late 1944, initial attempts to set up

a small production line near Gotha failed to materialize. During

this period, Mobel May, a small furniture firm near Tamm in Wurttemberg,

was brought into the program to manufacture wooden wing sections.

Because of Reichsmarschall Goring's influence the Ho 229 was

included in the Jager-Notprogramm (fighteiemergency program).

On September 21, 1944, the first forty production Ho 229 A-1s

were ordered. These were to be built by Gothaer Waggonfabrik74

Initially, the firm of Klemm, located at Boblingen, near Stuttgart,

was supposed to build twenty Ho 229s. Gotha was to build an additional

twenty aircraft. During late 1944, initial attempts to set up

a small production line near Gotha failed to materialize. During

this period, Mobel May, a small furniture firm near Tamm in Wurttemberg,

was brought into the program to manufacture wooden wing sections.

The fate of the Ho 229 V2's test pilot, Erwin Ziller, was sealed

when a flame-out occurred on February 26, 1945, during the landing

approach of his fourth flight. Unable to recover, Ziller crashed,

destroying the prototype. When the US 3rd Army Corps reached the

Gotha plant on April 14, 1945, three Ho 229 prototypes (V4, V5

and V6) were discovered in various stages of construction. The

Ho 229 V1 was captured at Leipzig. The Ho 229 V3, which was under

construction at the end of the war, was also seized, and was subsequently

shipped to the USA for evaluation.

Following his capture by members of the US. Seventh Army early

in May 1945, Reichsmarschall Hermann Goring was allowed to hold

a press conference for war correspondents at Kitzbahel. Champagne

was made available, and the Reichsmarschall was candid with his

views. "I am convinced that the jet planes would have won

the war for us if we had had only four or five months time,"

Goring said through the American interpreter. (Goring was, however,

fluent in English.) "If I had to design the Luftwaffe again,

the first airplane I would develop would be the jet fighter-then

the jet bomber, " he continued. Perhaps one of his more interesting

statements dealt with his preference for future aircraft design.

"According to my view, the future airplane is one without

fuselage (flying wing), equipped with turbine in combination with

the jet and propeller. " Following this interview, learning

of the cordial treatment afforded Goring, General Eisenhower cracked

down. The Reichsmarschall was unceremoniously and irrevocably

denied further activity on behalf of the Luftwaffe.

During November 1941 Galland left the famous fighter wing,

JG 26, to take over from Molders as General of the Fighters. Shortly

after consolidating his new command Galland asked that the technical

officer of JG 26, Obit. Walter Horten, be transferred to his staff.

Horten, with his elder brother, Reimar, had been working for about

ten years on the development of all-wing aircraft, building several

successful gliders to test his theories. Now, having the opportunity

to converse with some of the Luftwaffe's leading generals (an

opportunity further helped by the fact that he was married to

Udet's secretary), Horten managed to elicit verbal agreement from

Goring for him and his brother to set up a special group {Sonderkommando

9) at Gottingen to build more advanced all-wing aircraft. Of these,

the most important was the Ho IX fighter of which two prototypes

were to be completed, one as a glider, the other with twin turbojets.

After discovering the existence of the construction group early

in 1944, RLM officials ordered all further work to be stopped

as they had not been consulted. The Horten brothers immediately

sought a further interview with Goring who quickly gave them authorization

to continue their work.

In March 1944 the unpowered Ho IX V1 made its first flight

with Obit. Heinz Scheithauer at the controls, the airfield at

Oranienburg being used for the tests as that at Gottingen was

too small. This and subsequent tests were so successful that a

contract was placed for 40 powered aircraft with the Gothaer Waggonfabrik

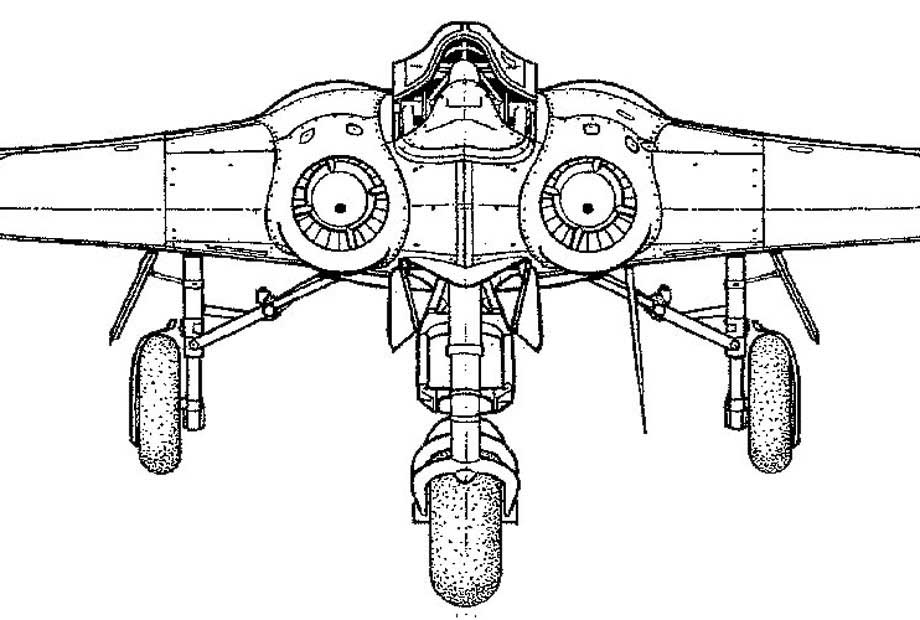

AG under the designation Go 229. The all-wing fighter was to be

powered by two BMW 003 turbojets situated one on each side of

the cockpit. Tubular steel was to be used for the construction

of the center section with wooden outer panels and plywood covering.

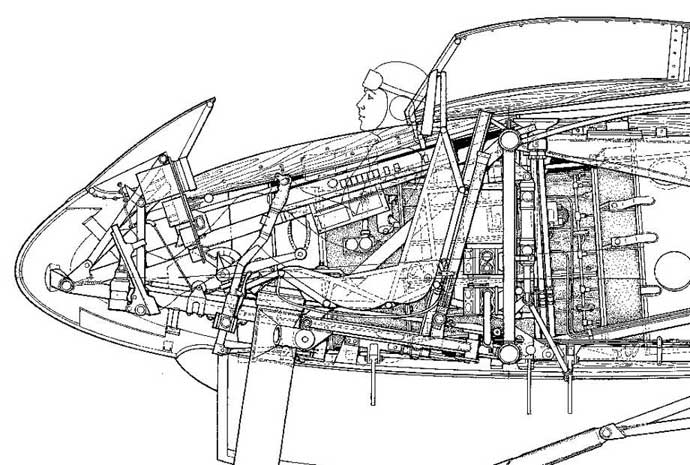

The cockpit was set well forward and the pilot was provided with

a spring-loaded ejector seat. Lateral and longitudinal control

was by means of elevons which occupied most of the trailing edge

of the wing, directional control being achieved by the aid of

flaps above and below the wingtips.

By August 1944 the Ho IX V2 was nearing completion at Gottingen

when the order came to replace the BMW 003 engines with a pair

of the more reliable, but considerably larger, Jumo 004s. This

order delayed completion by about seven weeks and it was not until

sometime in January, 1945, that the aircraft made its initial

flight from Oranienburg piloted by Fw. Erwin Ziller. Even at this

stage, considerable lateral instability was experienced, making

the aircraft a far from ideal gun platform.

Two further flights

followed, the fourth coming on February 26. Following a pass over

Bisping's funeral cortege, the port engine cut, leading Ziller

to attempt an emergency landing on a lengthened, grassed over,

portion of the runway. As the main wheels hit the ground, they

broke through a patch of ice, causing the aircraft to ground loop.

Ziller was killed. Despite the fact that the Gotha company had received the first

drawings of the Ho IX in July 1944, the third aircraft, the Go

229 V3, was still not complete when the war ended. The main reason

for this was that Gotha was more interested in promoting its own

P 60 delta wing fighter design than building the Ho IX.

Five further

prototypes were under construction as the war ended, the Go 229

V4 to V8. The first of these was a production prototype with a

new landing gear retraction system, armament, armor and self sealing

tanks. It was virtually complete when the war ended, but, like

the center section of the V5, it mysteriously disappeared before

the Friedrichsroda plant was captured by U.S. forces!

Construction

of the V6 and V7 also began, various armament combinations

being

proposed. These included four MK 108 or two MK 103 cannon

or two

MK 108s and two Rb 50/18 cameras. Some thought was also

given

to the production of a two-seat night fighter variant. At

one time it had been planned to transfer one of the Go 229

prototypes to the Versuchsverband OKL at Oranienburg, but

as has

been explained, none of these was completed. A proposal

was also

made in April 1945 to reequip 1./JG 400 with the Go 229.

At one time it had been planned to transfer one of the Go 229

prototypes to the Versuchsverband OKL at Oranienburg, but as has

been explained, none of these was completed. A proposal was also

made in April 1945 to reequip 1./JG 400 with the Go 229. When

U.S. troops captured Gotha's Friedrichsroda plant on April 14,

1945, the partly completed Go 229 V3 was found and transported

to the U.S. and is at present held in storage at NASM's Silver

Hill facility.

In your last email you mentioned some interest in the Horten glider which was the prototype for the Go 229. Using your model as a basis I've just

finished a 1/32nd scale model of the Horten Ho

9-V1 glider. The span is 19 7/8". The wing was built strictly

according to F.G. templates enlarged the only concession to size

was that I used poster board instead of paper. The conversion

consists of leaving off the engine housings and retractable landing

gear housing. The landing gear on the glider was fixed, the main

gear was housed in trapezoidal fairing's with the nose wheel exposed.

On my model the landing gear and pilots canopy are plastic everything

else is card. I must commend your design, in spite of the large

size and change of materials, the wing held its shape without

any internal bracing.

finished a 1/32nd scale model of the Horten Ho

9-V1 glider. The span is 19 7/8". The wing was built strictly

according to F.G. templates enlarged the only concession to size

was that I used poster board instead of paper. The conversion

consists of leaving off the engine housings and retractable landing

gear housing. The landing gear on the glider was fixed, the main

gear was housed in trapezoidal fairing's with the nose wheel exposed.

On my model the landing gear and pilots canopy are plastic everything

else is card. I must commend your design, in spite of the large

size and change of materials, the wing held its shape without

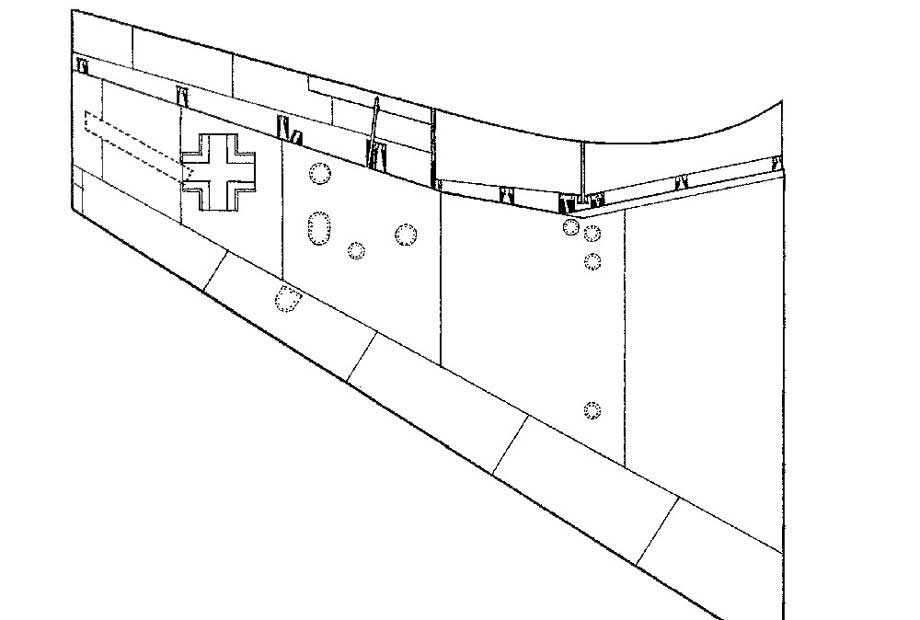

any internal bracing. From what I can see in the available black and white photographs, the glider was gray on top, probably light blue on the bottom with Balken crosses on top and bottom of wings. I hope in the future to photograph my 1/32nd Fiddlers Green based models and email you a copy. Regards, Jim

Horten IX

Soaring Wing' sailplane

The aircraft was of mixed construction (welded steel tube and

wood) and was covered with several layers of plywood of various

qualities, the outer layer being of the best quality. This method

of construction made radar detection of the aircraft extremely

difficult. The pilot was accommodated in a normal seated position.

The first flight of the V1 took place on March 1, 1944, at Gottingen

with Heinz Scheidhauer at the controls. Following several towed

takeoffs, the aircraft was sent to Oranienburg near Berlin for

flight testing, with Scheidhauer as pilot. A brief report submitted

by the DVL on April 7, 1944, indicated that the aircraft provided

an excellent gun platform.

In order to simulate the stabilizing effect of

the engines, which were absent from the V1, the aircraft's main

undercarriage legs were faired from the outset; only the aircraft's

nose wheel was retractable. On March 5 the nose gear failed after

it developed a wobble on Oranienburg's concrete runway. A special

pressure suit was to have replaced the absent cockpit pressurization,

but was never used in practice.

In order to simulate the stabilizing effect of

the engines, which were absent from the V1, the aircraft's main

undercarriage legs were faired from the outset; only the aircraft's

nose wheel was retractable. On March 5 the nose gear failed after

it developed a wobble on Oranienburg's concrete runway. A special

pressure suit was to have replaced the absent cockpit pressurization,

but was never used in practice.

The machine was sent to Brandis, where it was to

be tested by the military and used for training purposes. It

was found there by soldiers of the US 9th Armored Division at

the end of the war and was later burned in a "clearing action.

Designer's Building Tips

During mock-ups I found it easiest to attach the second wing by sliding the wing ass'y onto the already glued up tabs and then applying light pressure just inside the joint at the leading and trailing edge of the fuselage. This "puffs up" the fuselage, making it grab hold of the wing tabs. Watch alignment closely! Alene's Tacky, WeldBond or other quick setting glue works well.

FWIW, if you don't feel comfortable with this, you can cut a hole in the gray area where the main landing gear housing covers and get a finger in there. This area is completely covered anyway.

If there's enough of a problem here I can even draw a cut-out area right on the model for this purpose. Chauncy Green.

BB... Question:

So, how are you putting the two halves together? The pix looks like a butt joint. Is that the case??

So, how are you putting the two halves together? The pix looks like a butt joint. Is that the case??

Chauncy:...Haven't decided for sure yet,

but am leaning towards a double connecting strip. I've tried tabs

on one half but I don't think that will cut the mustard. We'll

see, things have a way of changing.

First attempt was a tracing as RM described. With

an airfoil/chord this thick the problem for me was getting a

straight/true joint at the wing root. Which in this case is the

center of the whole shabang. In addition that center section

has a different profile than the outer

sections. The joint between them also needed to be straight to look right. After stretching and poking these joints for a couple of weeks I'm finally getting "close enough for government work". ;-)

sections. The joint between them also needed to be straight to look right. After stretching and poking these joints for a couple of weeks I'm finally getting "close enough for government work". ;-)

One day I'm liable to be in the shower and the

force of the water on my head may knock some sense into me and

I'll get another brainstorm. This is how the Flea wing curve

and the Trieb rotating collar came to me. ...No, really. ;-)

FEB 18 addition....

One of the first things I've been doing when starting a design is trolling the web for info, pictures, 3-views, etc. It's like having an "off-brand" encyclopedia right at my fingertips. Still need the books though.

As far as progress on the 229 goes, I've joined

the two halves of the center (fuse) section together at the bottom-rear

and will use tabs up one side of the center joint to make it

come together like a zipper. ;-) I did a test build with two

separate sections and a connecting

As far as progress on the 229 goes, I've joined

the two halves of the center (fuse) section together at the bottom-rear

and will use tabs up one side of the center joint to make it

come together like a zipper. ;-) I did a test build with two

separate sections and a connectingstrip and it was a bit difficult getting things lined up and joined together tightly.

I'm working on the engine nacelles now. Kinda tough

because of the odd angle that the engines were mounted on. (Down

and In). It's based on the V3 that unlike the Fly model Nachtjager,

which is based on the V7, has full-length nacelles instead of

just humps on the upper wing. It'll come, soon as I get some

time to do some testing/adjusting. ;-)

As far as color schemes go, I'm leaning toward

the one depicted in the 3-view on page 250 of the book "Warplanes

of the Third Reich" by William Green. Doc (or anyone else)

if you have this one, can you be any help with the colors as

it's printed in B&W. RLM 74, 75, 76 again? Hard for me to tell whether it's the RLM gray shades or

green.

I've attached a graphic that

is just nothing but "scary" to me. I pulled this off

Usenet some time ago and wish I  knew who rendered it

(so I could give credit) because it's really well done. Pretty

cool composite of a real B2 being stalked by a pair of rendered

ho-229s. knew who rendered it

(so I could give credit) because it's really well done. Pretty

cool composite of a real B2 being stalked by a pair of rendered

ho-229s. Every design I've done so far for Fiddlers Green has been of a subject that I have little actual knowledge of but have grown to love through learning and the more I learn about these Horten brothers and they're work, the more amazed I am. Think about it... that's a billion dollar airplane being stalked by something that flew off the drawing boards fifty years earlier! Yep, those 229s with their wooden construction were pretty "stealthy" too and just as fast as a B-2. Chauncy |

The Experimental Horten H-IX

Glider...The very advanced pre-war Horten 'soaring wing' Glider The Experimental Horten H-IX

Glider...The very advanced pre-war Horten 'soaring wing' GliderThe aircraft was of mixed construction (welded steel tube and wood) and was covered with several layers of plywood of various qualities, the outer layer being of the best quality. This method of construction made radar detection of the aircraft extremely difficult. The pilot was accommodated in a normal seated position. The first flight of the V1 took place on March 1, 1944, at Gottingen with Heinz Scheidhauer at the controls. Following several towed takeoffs, the aircraft was sent to Oranienburg near Berlin for flight testing, with Scheidhauer as pilot. A brief report submitted by the DVL on April 7, 1944, indicated that the aircraft provided an excellent gun platform.

In order to simulate the stabilizing effect of

the engines, which were absent from the V1, the aircraft's main

undercarriage legs were faired from the outset; only the aircraft's

nose wheel was retractable. On March 5 the nose gear failed after

it developed a wobble on Oranienburg's concrete runway. A special

pressure suit was to have replaced the absent cockpit pressurization,

but was never used in practice.

The machine was sent to Brandis, where it was to

be tested by the military and used for training purposes. It

was found there by soldiers of the US 9th Armored Division at

the end of the war and was later burned in a "clearing action."

|

| Northrop N9M-B Flying Wing The N9MB was built in 1944 as the last of four 1/3 scale prototypes of the B35/YB49 Flying Wing Bombers. It was built to  test the

full power irreversible hydraulic

flight control system used in the B35 bomber and to check out

pilots prior to flying the big wings. This is the only 60 foot

N9M known to exist. Ed Maloney obtained it in the 1950's when

it was being scrapped at Edwards Air Force Base. The N9M was test

flown by both Bob Hoover and Chuck Yeagar during Air Force test

flights. An earlier model N1M 30 foot wing is on display in the

Smithsonian Museum, but all of the full scale bombers were scrapped. test the

full power irreversible hydraulic

flight control system used in the B35 bomber and to check out

pilots prior to flying the big wings. This is the only 60 foot

N9M known to exist. Ed Maloney obtained it in the 1950's when

it was being scrapped at Edwards Air Force Base. The N9M was test

flown by both Bob Hoover and Chuck Yeagar during Air Force test

flights. An earlier model N1M 30 foot wing is on display in the

Smithsonian Museum, but all of the full scale bombers were scrapped.The N9MB took 13 years and over 20,000 man hours to rebuild by a group of volunteers at Planes of Fame, and was supported by aircraft component manufacturers. Two of the volunteers were original "Norcrafters" who worked on the wing during the original construction. The outer wings are wood construction and the engines are mounted in a steel frame center body. The engines are the original eight cylinder Franklin's, which are supercharged to obtain 325 horsepower. (Less than 20 of these engines were built by Franklin in the 1940's.) The N9MB first flew November 11, 1994, flown by Don Lykins. This plane is based at the Fighter Jets Museum in Chino. |

The Horten Ho 229:

(often erroneously

called Gotha Go 229 due to the identity of the chosen manufacturer of

the aircraft) was a late-World War II flying wing fighter aircraft,

designed by the Horten brothers and built by Gothaer Waggonfabrik. It

was a personal favourite of German Luftwaffe chief Reichsmarschall

Hermann Gring, and was the only plane to be able to meet his infamous

performance requirements. In the 1930s the Horten brothers had become

interested in the all-wing design as a method of improving the

performance of gliders. The all-wing layout removes any "unneeded"

surfaces and –in theory at least– leads to the lowest possible drag. For

a glider this is important, with a more conventional layout you have to

go to extremes to reduce drag and end up with long wings. If you can

get the same effect with a different layout, you end up with a similarly

performing glider that's sturdier. Years later, in 1943 Reichsmarschall

Gring decided that all future aircraft purchased by the Luftwaffe were

required to fly a 1000 kg load over 1000 km at 1000 km/h – the so called

1000/1000/1000 rule. At the time there was simply no way to meet these

goals; jet engines could give the performance required, but swallowed

fuel at such a rate that they would never be able to match the range

requirement.

The Hortens felt that the low-drag all-wing design could meet all of the goals – by reducing the drag cruise power could be lowered to the point where the range requirement could be met. They put forward their current private (and jealously guarded) project, the Ho IX, as the basis for a fighter. Reichsmarschall Gring believed in the design and ordered the aircraft into production at Gotha as the RLM GL/C List designation of Ho 229 before it had taken to the air under jet power. Flight testing of the Ho IX/Ho 229 prototypes began in either in December 1944 or January 1945, and the aircraft proved to be even better than expected. There were a number of minor handling problems but otherwise the performance was outstanding. Gotha appeared to be somewhat upset about being ordered to build a design from two "nobodies" and made a number of changes to the design, as well as offering up a number of versions for different roles.

Several more prototypes, including those for a two-seat night fighter, were under construction when the Gotha plant was overrun by the American troops in April. The Ho 229 A-0 pre-production fighters were to be powered by two Junkers Jumo 004B turbojets with 1,962 lbf thrust each. The maximum speed was estimated at an excellent 590 mph at sea level and 607 mph at 39,370 ft. Maximum ceiling was to be 52,500 ft, although it's unlikely this could be met. Maximum range was estimated at 1180 miles, and the initial climb rate was to be 4330 ft/min . It was to be armed with two 30 mm MK 108 cannon, and could also carry either two 500 kg bombs, or twenty-four R4M rockets. It was the only design to meet the 1000/1000/1000 rule, and that would have been true even for a number of years after the war. But like many of the late war German designs, the production was started far too late for the plane to have any effect. In this case none saw combat.

The Hortens felt that the low-drag all-wing design could meet all of the goals – by reducing the drag cruise power could be lowered to the point where the range requirement could be met. They put forward their current private (and jealously guarded) project, the Ho IX, as the basis for a fighter. Reichsmarschall Gring believed in the design and ordered the aircraft into production at Gotha as the RLM GL/C List designation of Ho 229 before it had taken to the air under jet power. Flight testing of the Ho IX/Ho 229 prototypes began in either in December 1944 or January 1945, and the aircraft proved to be even better than expected. There were a number of minor handling problems but otherwise the performance was outstanding. Gotha appeared to be somewhat upset about being ordered to build a design from two "nobodies" and made a number of changes to the design, as well as offering up a number of versions for different roles.

Several more prototypes, including those for a two-seat night fighter, were under construction when the Gotha plant was overrun by the American troops in April. The Ho 229 A-0 pre-production fighters were to be powered by two Junkers Jumo 004B turbojets with 1,962 lbf thrust each. The maximum speed was estimated at an excellent 590 mph at sea level and 607 mph at 39,370 ft. Maximum ceiling was to be 52,500 ft, although it's unlikely this could be met. Maximum range was estimated at 1180 miles, and the initial climb rate was to be 4330 ft/min . It was to be armed with two 30 mm MK 108 cannon, and could also carry either two 500 kg bombs, or twenty-four R4M rockets. It was the only design to meet the 1000/1000/1000 rule, and that would have been true even for a number of years after the war. But like many of the late war German designs, the production was started far too late for the plane to have any effect. In this case none saw combat.

The H V was designed from the outset as a powered aircraft using two Hirth H.M. 60 R motors driving oppositely rotating propellers. It has a span of 52.5 feet, aspect ratio of 6:1, and a quarter chord sweepback of 32 degrees. Engines were completely buried and drove propellers on extension shafts raised relative to the engine crankshaft and driven through a reduction gear. The undercarriage was of fixed tricycle type with castoring nose wheel and trousered main wheels. The nose wheel actually too 55% of the static weight when on level ground.

Three examples were built. The first, built at Ostheim in 1936 was constructed of plastic material with riveted sheet plastic covering. Pilot and passenger were contained entirely in the wing contour and the nose wheel was retractable. This aircraft crashed on its first flight, due mainly to its unorthodox waggle-tip control. The second version used more normal control methods and conventional construction, it was started in 1937 and flew successfully. In 1941 it was completely rebuilt as a single-seater, but retained the same control system.

Controls:

Controls:In its original form the H V was fitted with waggle tip control in which the fore and aft sweep of the wing tips was geared to the stick, producing incidence change by a skew hinge arrangement. The aircraft crashed on it first flight due to the control taking charge after a bounce during landing. The reason for the accident was obscured by a failure of one engine but the control system was not regarded as satisfactory by the Hortens who later developed the idea further on an H III. They considered that damping is necessary to prevent the tips oscillating under suddenly applied acceleration (as occur during take off and landing). The second aircraft in both its forms had a two stage elevon control rather similar to the H III.

The outer control flaps had a 20% Frise nose and assymmetrically geared tube to compensate the non linear moment characteristics of the nose balance. The inner flap pair had round noses.

Split trailing edge flaps were fitted to the center section, the flap between the engines lowering to 60° and the part outboard to 45°. The inner elevon flaps dropped to 30° when the center section flaps were lowered and still operated as elevons about this new zero position. The idea of using graded flap deflections originated from a hunch of the Hortens that the sudden discontinuity and greater spanwise flow with ungraded flaps might cause stability and control troubles. They later found that this fear was unfounded and gave up the graded deflection principle. Rudder control on the second two aircraft was by split nose flaps on the H III pattern.

Flying Characteristics:

A great deal of flying was done on the second and third H V’s, including about twenty flights on the latter in 1943 by Prof. Stuper of A.V.A. Gottingen. We questioned him extensively about his impressions of the aircraft (Sept. 21, 1945), because it was the most recent Horten product he had flown. The Hortens themselves had lost interest in the H V because later designs incorporated many improvements. Stuper has also flown the H IIId with Walter Mikron engine.

Tests at A.V.A. were undertaken at the request of D.V.L. who wanted information on single engine characteristics and an unbiased comparison between tailless and conventional handling qualities. Stuper’s comments were as follows:

Stability:

Longitudinal dynamic stability was good and no fundamental different from a conventional aircraft could be noticed. In rough air he thought it had a more abrupt pitch response than normal, which was only a disadvantage if gun platform steadiness was needed. (Walter Horten thought this effect might be due to the low wing loading (6 lb/sq.ft.) on the H V and Stuper agreed that this might be so). Lateral stability appeared satisfactory. No tendency to “dutch roll” instability was found and no arratic changes of heading due to low Nv and Yv were noticeable. Stuper was in fact expecting trouble from this source but failed completely to find any. He added that his impressions were purely qualitative as they had no time to instrument the aircraft.

Controls:

Controls were light and effective, with the exception of the rudder, which was heavy and not effective enough. Aileron was heavier than the elevator “in the ratio 4:3”. With the stick back, aileron movement was restricted, which Stuper thought a bad point since plenty of aileron was useful in an approach in gusty weather. The aircraft was in trim virtually over the whole speed range without movement of the elevator trimmer. When flaps were lowered there was a slight nose heavy tendency which could easily be held.

Summing up:

Stuper said that aileron and elevator control were quite normal but rudder control needed improvement.

Stall:

Behavior at the stall (flaps down) was very satisfactory, the nose dropped gently and the aircraft gained speed. Wing dropping could be induced if the aircraft was stalled in a yawed attitude but normally the wings remained level and ailerons still effective, thought restricted in movement. The stall was reached with the stick not quite fully back; only one CG position was tested. Stalling speed was about 70 kph.

Single Engine Flight:

Flight on one engine was possible, without rudder, at 120 kph by flying with 10 degrees of bank and 80% aileron. Rudders were not used much because they were so heavy, although Walter Horten claimed that at 130 kph single engine flight could be maintained on rudder only (engine nearly at full power) if the pilot was strong enough.

Landing and Take-off

Ground maneuvering was easy using throttles and wheel brakes. During take-off the aircraft could quite easily be kept straight until the drag rudders became effective, and flew itself off the ground without assistance from the pilot - in fact it made very little difference what the pilot did with the controls during take-off. There was no tendency to bounce during the ground run. R.L.M. require that for normal tricycles, it should be possible to left the nose wheel before take-off speed is reached; Walter Horten thought this was unnecessary if the aircraft would fly itself off. Landing was quite straightforward and normally the aircraft settled down on all wheels at once. Stuper thought it was not possible to land on the main wheels first because the ground incidence was too high.

Baulked Landing

Stuper had done some tests of take-off performance with flaps down, which resulted in his flying into a hanger and terminating the A.V.A.test programme. Apparently he landed and immediately (Walter Horten said not immediately) opened up to take-off again - after 530 meters he was 8 meters high and at that point entered the hanger. The airborne distance was about 150 meters. Although the split flaps in front of the propellers caused poor thrust, there were apparently no vibration problems.

Summarizing his impressions on the H V, Stuper said that it was hardly fair to compare it with conventional aircraft with many years more development behind them but it was nevertheless, a good example of tailless design and a perfectly practical aeroplane - if anyone wanted tailless aeroplanes. His main suggestion for improvement was in the rudder control.

Horten VI

In

general,

the layout of this aircraft was very similar to the H IV. The span was

increased to 78.7ft accompanied by a decrease of 5% in wing area,

giving an aspect ratio of 32.4.

general,

the layout of this aircraft was very similar to the H IV. The span was

increased to 78.7ft accompanied by a decrease of 5% in wing area,

giving an aspect ratio of 32.4. The object in building the H VI was to achieve the most efficient high performance sailplane regardless of cost. Two were built and the first was tested late in 1944. It was performance tested by the relative sinking speed method previously described, using a calibrated H IV for the second glider. The Hortens were very pleased because it was better than the D 30 (same span and wing loading) over the whole speed range.

Aerodynamically there were no new features of special interest compared with the H IV. Wing sections and control systems remained the same. The structural design had to be refined in order to get sufficient bending strength in the very thin cantilever. The main spar was made up of laminations of plain wood and “bignefel” (a compressed impregnated wood) to give extra strength at the root, and a special wing root fitting using four taper pins in place of the normal two was devised to distribute the concentrated loads at the root. The torsion box design was modified also to increase the wing torsional stiffness, since at high speed it had been found that an unstable short period longitudinal oscillation, involving wing twist, could develop. The speed at which the damping of this oscillation became zero on the H VI was found to be about 112mph.

The H VI is of interest only as a high performance sailplane for record breaking purposes. It is too costly and difficult to handle for general use. The second aircraft of this type to built was found intact, by the writer, near Horsfeld; the first aircraft was found destroyed neat Gottingen, where it had been flying.

Horten VII

The H VII was projected in 1938 and the first of the type was built by Peschke at Minden in 1943. It bears a general resemblance to the modified H V in layout and control design and used the same outer wing panels: the span was the same (16m) the sweepback slightly greater (34 degrees) and aspect ratio 5.8 instead of 6.1. Its function seems to have been that of a high speed two-seater commun- ications aeroplane and trainer for tailless pilots. Engines were Argus AS 10 C of 240 hp.

The H VII was projected in 1938 and the first of the type was built by Peschke at Minden in 1943. It bears a general resemblance to the modified H V in layout and control design and used the same outer wing panels: the span was the same (16m) the sweepback slightly greater (34 degrees) and aspect ratio 5.8 instead of 6.1. Its function seems to have been that of a high speed two-seater commun- ications aeroplane and trainer for tailless pilots. Engines were Argus AS 10 C of 240 hp.

Altogether two were completed and flown and a

third was nearing completion at Minden when the district was occupied

by the Allies. Two aircraft were damaged beyond repair and the third

fell into Russian hands at Eilenburg.

Controls

Single stage elevon control was used on the H VII with 25% Frise nose and geared tab. Inboard of the elevons was a plain flap and in the middle trailing edge split flaps extending for the full width of the center section. Initially the graded flap angle principle was used, the part between the engines opening to 60 degrees, between the engine and the outer wing panels to 45 degrees, and the plain flap on the wing lowering to 20 degrees. When R.L.M. ordered the design in quantity however they asked for it to be simplified and for landing speed to be raised to give pilots more realistic training for high speed aircraft. The plain flap was accordingly locked up on the second aircraft and omitted altogether on the series production model.

Plug spoiler drag rudders of the H IV type were used on the first aircraft. These tended to suck open and had to be held closed by springs. They were not very satisfactory from the point of view of control forces and feel, and after about 10 flights they were scrapped and replaced by a new “trafficator” design. This was simply a bar which projected 15.75 inches in a spanwise direction from the wing tip when rudder was applied and retracted flush with the wing surface when not in use. Fig 17 (ed. - not reproducible) shows the rudder in open and closed positions but without the vent holes, which were cut to adjust aerodynamic balance. The vent holes allowed flow through the bar and deflected the flow sideways to generate a self-closing aerodyn amic

force. This was supplemented by a spring loading and the two

components adjusted to give satisfactory feel on the rudder bar. This

type of rudder was claimed to be cheap and easy to make and generally

more satisfactory then previous designs.

amic

force. This was supplemented by a spring loading and the two

components adjusted to give satisfactory feel on the rudder bar. This

type of rudder was claimed to be cheap and easy to make and generally

more satisfactory then previous designs.

Structure:

This followed normal Horten practice, the center section being of welded tube construction and the wings of single spar wooden construction with ply covering. The undercarriage was a completely retractable four-wheel layout, the front wheel pair taking about 50% of the total weight when resting on level ground. The constant speed airscrews were driven through extension shafts with a thrust ball bearing and rubber flexible coupling at the engine end and a self aligning ball bearing at the airscrew end mounted on a cantilever form the main structure.

Aerodynamic Design:

Outer wing panels were of the same aerodynamic shape as those of the H V. At the center line the section was 16% thick with 1.8% camber (zero Cmo) graded to 8% symmetrical tip sections. Wing twist was 5 degrees; 2 degrees linearly and 3 degrees parabolically distributed. The aircraft trimmed with elevons neutral at 162 mph.

Controls

Single stage elevon control was used on the H VII with 25% Frise nose and geared tab. Inboard of the elevons was a plain flap and in the middle trailing edge split flaps extending for the full width of the center section. Initially the graded flap angle principle was used, the part between the engines opening to 60 degrees, between the engine and the outer wing panels to 45 degrees, and the plain flap on the wing lowering to 20 degrees. When R.L.M. ordered the design in quantity however they asked for it to be simplified and for landing speed to be raised to give pilots more realistic training for high speed aircraft. The plain flap was accordingly locked up on the second aircraft and omitted altogether on the series production model.

Plug spoiler drag rudders of the H IV type were used on the first aircraft. These tended to suck open and had to be held closed by springs. They were not very satisfactory from the point of view of control forces and feel, and after about 10 flights they were scrapped and replaced by a new “trafficator” design. This was simply a bar which projected 15.75 inches in a spanwise direction from the wing tip when rudder was applied and retracted flush with the wing surface when not in use. Fig 17 (ed. - not reproducible) shows the rudder in open and closed positions but without the vent holes, which were cut to adjust aerodynamic balance. The vent holes allowed flow through the bar and deflected the flow sideways to generate a self-closing aerodyn

amic

force. This was supplemented by a spring loading and the two

components adjusted to give satisfactory feel on the rudder bar. This

type of rudder was claimed to be cheap and easy to make and generally

more satisfactory then previous designs.

amic

force. This was supplemented by a spring loading and the two

components adjusted to give satisfactory feel on the rudder bar. This

type of rudder was claimed to be cheap and easy to make and generally

more satisfactory then previous designs.Structure:

This followed normal Horten practice, the center section being of welded tube construction and the wings of single spar wooden construction with ply covering. The undercarriage was a completely retractable four-wheel layout, the front wheel pair taking about 50% of the total weight when resting on level ground. The constant speed airscrews were driven through extension shafts with a thrust ball bearing and rubber flexible coupling at the engine end and a self aligning ball bearing at the airscrew end mounted on a cantilever form the main structure.

Aerodynamic Design:

Outer wing panels were of the same aerodynamic shape as those of the H V. At the center line the section was 16% thick with 1.8% camber (zero Cmo) graded to 8% symmetrical tip sections. Wing twist was 5 degrees; 2 degrees linearly and 3 degrees parabolically distributed. The aircraft trimmed with elevons neutral at 162 mph.

Performance

The following performance data were quoted by Reimar Horten from memory:

|

|

| Flying weight (minimum) |

6,393 lbs

|

| Flying weight with full equipment |

7,055 lbs

|

Engines 2 x 240 hp Argus AS 10 C (normally aspirated)

|

|

| Sea level (crusing speed (180-200 hp per engine) |

193 mph

|

| Sea level (top speed) |

211 mph

|

| Normal take-off speed |

68 mph

|

| Ground run |

820 feet

|

| Sea level rate of climb at 112 mph (full power) |

23 ft/sec

|

| Ceiling |

21,325 feet

|

Handling Characteristics

Reimar Horten told us that prior to the first flights b Scheidhauer on the H VII, his brother Walter had supervised the CG’ing of the aircraft ad mistakenly put ballast in the nose because the measurements were made with a steel tape with 10 cm missing from the end. Scheidhauer’s comments to us were that the aircraft had to be brought in at a minimum speed of 120 kph, with the stick nearly right back, if the nose was to be lifted for the hold off; the aircraft then floated (stick fully back) until 90 kph before touching down. Normal take-off procedure was to accelerate to 120 kph and then pull the stick back when the aircraft immediately took off and climbed away. Apparently it could be unstuck at 90 kph by pulling back hard but would not climb until 120 kph had been reached. It was impossible to stall the aircraft with the CG in this position; the general behavior was said to be “good natured”.

Walter flew the H VII (with the CG in its correct position) on 30-40 occasions, a total flying time of about 18 hours. (Scheidhauer’s time was also about 18 hours). Apparently the change in CG brought the approach speed down to about 100 kph and the aircraft could be touched down on the rear wheels. It was not certain that a complete stall could be produced in steady flight. With the stick fully back the aircraft sank on an even keel with fair lateral control. Lateral control was pleasant, the 25% Frise balance eliminated adverse yaw and virtually enabled flying on two controls.

Tests with the “trafficator” drag rudder showed that single engine flight could be maintained with half rudder and a little sideslip; turns could be made in level flight against the dead engine. On one test the pilot was carrying out a single engine approach when he realized that he had stopped the engine supplying the undercarriage hydraulics and could not lower the wheels. He was able to climb away, start the dead engine and made a normal landing.

Thanks to Wayne Cutrell for this diorama |

Tim Allen sends in this enlarged Horten Ho229. Thanks Tim! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

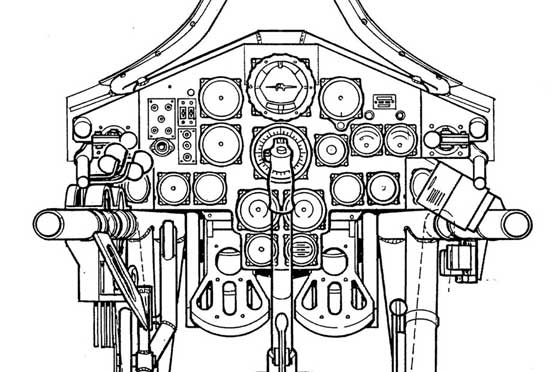

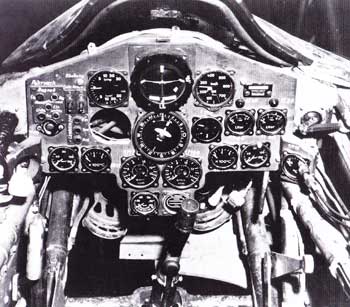

The Cockpit of the Horten Ho 229.

|

Specifications for the Horten Ho229

|

Length: 24 ft 6 in

Wingspan: 55 ft Height: 9 ft 2 in Wing area: 540.35 ft² Empty weight: 10,141 lb Loaded weight: 15,238 lb Max takeoff weight: 17,857 lb Powerplant: 2× Junkers Jumo 004B turbojet, 1,956 lbf each Performance Max speed: 607 mph at 39,370 ft Combat radius: 620 mi Ferry range: 1,180 mi Service ceiling: 52,000 ft Rate of climb: 4,330 ft/min Wing loading: 28.2 lb/ft² Thrust/weight: 0.26 Armament 2 × 30 mm MK 108 cannon R4M rockets 2 × 500 kg (1,100 lb) bombs |

|

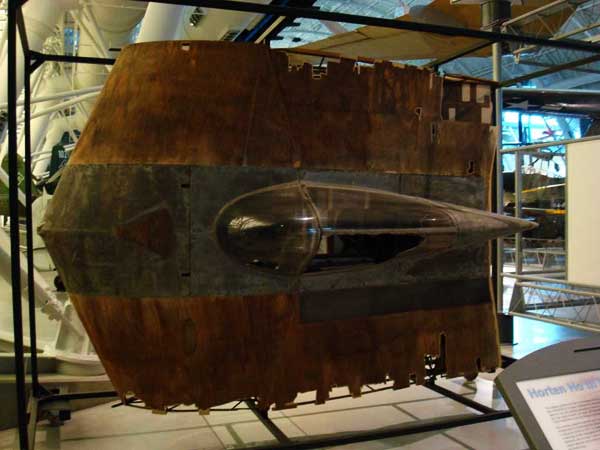

The Horten Ho III center section on display at the NASM.

|

|

When

U.S. troops captured Gotha's Friedrichsroda plant on April 14,

1945, the partly completed Ho 229 V3 was found and transported

to the U.S. and, as shown here, is/was held in storage at NASM's Silver

Hill facility.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment